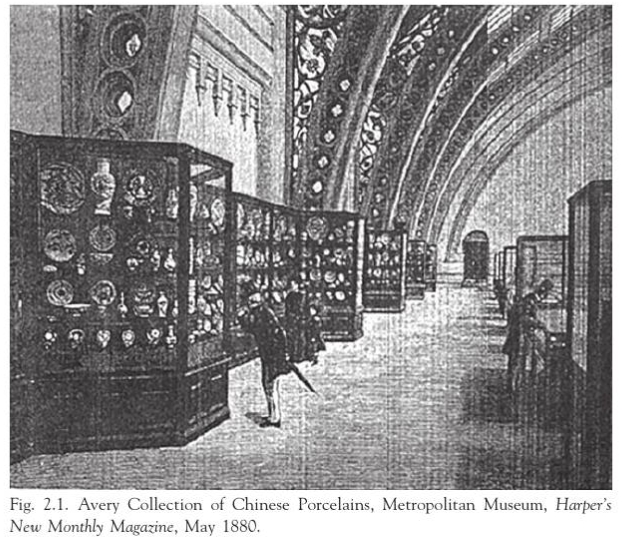

It was very surprising to learn that Chinese art/objects were key in changing the American definition of what art should be. At first, Americans during the Victorian era believed that “fine art conveyed … a seemingly transparent message of morality”, and even had a hard time “separating aesthetic categories from value judgments” (73). When Chinese art was introduced to museums, doubts began to surface about what art was. “The initial Chinese collections seen by Americans … were eclectic mixtures of traditional Chinese art, cultural artifacts, and fantastic polyglot objects created in China specifically for Western taste. None of these objects fit comfortably into the predominant Ruskinian paradigm, and … they were [instead] used as examples for industrial education” (74). However, their continued presence in museums despite being an unfamiliar subject allowed people to slowly understand and appreciate its distinctness, so much so that it “gained the status of fine art” (74).

Americans, and many Westerners for that matter, appreciate art for its beauty and aesthetic values, understanding it more for its emotional/personal attraction instead of its historical or cultural significance. In Collecting Objects/Excluding People, Lenore Metrick-Chen explains that, in the middle of the 19th century, Americans especially “esteemed artworks and architectural decorations that incorporated easily understood symbols embodying idealized public virtues and other highly principled messages” (75). While it was more difficult for Chinese objects to change their definition of what art is, and were not included in the “American moral canon of art and objects”, the opposite could be said about Japanese objects. Idealizing the Japanese as “virtuous and artistic, albeit naive” (78), Americans were fascinated with the “Japanese style” incorporated in the objects, which, coincidentally or not, looked like the Gothic style praised by art fanatics at the time. The Gothic style was a highly esteemed art style as it symbolized “the culminating manifestation of a society unified by religious faith” (78), and it helped pave way for Americans to begin collecting Japanese objects and even use the Japanese style. However, as mentioned previously, Americans did not understand the cultural integrity of Japanese objects and only appreciated the “Japanese aesthetic”.

Because there was a lack of distinction between Chinese and Japanese art, the purchase and collection of Chinese objects increased quite a bit. For example, “A list of Asian items in American museum collections compiled in 1929 showed the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston owned 88,074 Japanese and 4,393 Chinese objects” (80). While there were significantly more Japanese objects than Chinese objects, and they weren’t perceived as differently from their Japanese counterparts, we still managed to see a continual increase in the Chinese collection.

Bibliography

Metrick-Chen, Lenore. Collecting Objects/excluding People : Chinese Subjects and American Visual Culture, 1830-1900. Albany N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 2012.