In 617, Li Yuan, a Sui general and, later, the Duke of T’ang, joined the scores of rebels, who had arisen in the waning years of the Sui dynasty, and marched straight for the Sui capital, Chang’an. His armies overwhelmed its defenses and took control of the city. He would then, for six months, relegate the emperor to the position of Taishang Huang (or retired emperor), devise a series of plans, and, ultimately, establish a new dynasty that would last for almost three centuries and would rank alongside the Han dynasty as one of China’s two golden ages. Why was it so successful? The Sui dynasty was plagued with death, forced labor, and heavy taxes, and many wanted to move away from it. The people merely sought peace, prosperity, and safety. Despite being a turning point in China’s history, the T’ang pacification effort was marked by considerable restraint. Defeated troops, those who surrendered voluntarily with their armies and territory, and even prisoners of war were given amnesty. In fact, they were often absorbed into the T’ang army. The armies of important rebel leaders were added as whole units under the same commanders, a situation which no doubt contributed to the willingness of rebel leaders to transfer their allegiance to the T’ang. From the very beginning, the T’ang dynasty was built on the promise of safety and protection. In order to appease social tensions in the newly pacified T’ang territories, a new code was created aiming to smooth earlier laws and reduce/lessen physical punishments. However, these set of laws and codes would prove to be the dynasty’s greatest weakness and, unavailingly, its inescapable doom.

In the first years of the dynasty, a series of criminal codes and administrative statutes were established in order to govern the empire effectively. The criminal code, entitled the T’ang Code, is said to have been masterminded by the T’ai-tsung emperor’s (627-649) brother-in-law, Zhangsun Wuji, who was one of the most powerful statesmen at the time. It described the “Ten Abominations”, or the ten most serious offenses a person could commit, expounding on the general principles of criminal law and setting the punishment for each such offense. It is stated that, during the reigns of the emperors Yao and Shun, there were very few crimes owing to the high moral standards that were followed in those days. The view of society expressed in the Code suggests that those ancient times were a golden age from which there has been a steady decline. With this decline, the “standards of morality were no longer sufficient to maintain order, and so laws became necessary. Thus morality and law are the two principal supports of society—morality first, but if it fails then punishment is the answer” (Wallace 9). The T’ang criminal procedure was generally logical, thorough, and provided quite a few protections for the accused, but, ultimately, the basic rule was that criminal offenses needed to be prosecuted through set rules of criminal procedure. Certainly one of the aims of the Code is to act as a deterrent; to fill the prospective law-breaker with fear for the consequences.

The most pressing problem for the early T’ang dynasty was the restoration of fiscal solvency. The government’s granaries and treasuries were basically empty at the dynasty’s founding. The state, therefore, reinstituted the “equal fields” system because it ensured a steady flow of tax revenues. Emperor Xuanzong of T’ang (712–756), also called Illustrious August, sent agents out to find and reregister runaway households to increase revenues. These were families who had fled due to the Khitan and Turkish invasions during Empress Wu’s reign, forced military service, famines, and other hardships in the north. Most of the peasants fled south to occupy previously uncultivated lands and, being unregistered there, were able to evade taxation. With the help of the T’ang Code, the government offered those who voluntarily surrendered six years of exemption from taxation and compulsory labor in return for a payment of 1,500 coppers. As a result, the government “reregistered more than 800,000 families and took in more than 1 billion cash by 724 [AD]” (Benn 7). Land reclamation increased agricultural productivity, and a rationalization of the canal system reduced the cost of transporting grain and other commodities. Trade became an option. Furthermore, the T’ang Code helped “the emperor’s government efficiently maintain law and order so that there was little banditry. Travel was safe and trade flourished” (Benn 7). With economic prosperity, China was able to succeed in foreign affairs and territorial expansion. To continue its economic, political, and military expenditures, they heavily relied on the Silk Road, which proved to be a very important doorway to cultural and religious expansion.

The two main religions that dominated the T’ang dynasty were Buddhism and Confucianism; however, many were especially interested in Buddhism, and thousands of Chinese pilgrims journeyed to Central Asia and even to India to visit holy places, study, and bring back Buddhist scriptures. Emperor T’ang was infamous for his prejudice against Buddhists, having outlawed the religion originally, but Illustrious August approved the religion and revived it in China. Buddhism attracted many Chinese minds, leading them to establish Buddhist monasteries and attract students from other countries. The religion was at its peak during this period, and, after three hundred years of political unrest, the empire was finally reunified. Buddhist monasteries acquired great amounts of wealth in the form of land, grains, and precious metals, and the religion gained much popularity amongst the T’ang rulers. However, problems began to arise. Various wealthy and powerful families began to establish Buddhist monasteries as a means of evading taxation, and “defrocked more than 30,000 spurious monks, returning them to lay life and the tax rolls” (Benn 7). As a result, Illustrious August took measures against the Buddhist church and forbade these families from creating any more monasteries. Unfortunately, because of how the T’ang Code was set up, he could not really do this without breaking several rules. The articles in the T’ang Code were very specific, and therefore the Code foresaw a possibility of a criminal offense not being covered by a specific article of the T’ang Code. If this happened, then the magistrate would not be able to cite an existing article of the T’ang Code per the requirements. While some of China viewed Buddhism as a positive way to establish control and order as Taoism and Confucianism did in the past, many believed Buddhism to be poisonous to Chinese culture and undermined Confucianism teachings. As a result, successors of the throne would misinterpret his actions and, consequently, lead to several recorded moments of anti-Buddhist persecution in China, so much so that masses were slaughtered, wars waged, and the empire nearly went bankrupt.

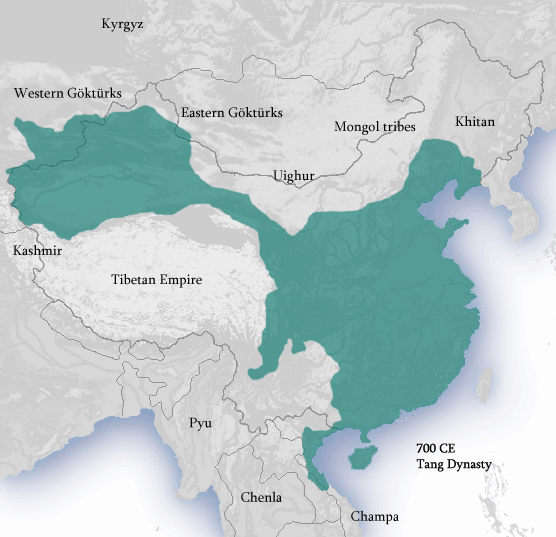

Following the major set-backs suffered in the final decades of the seventh and the beginning of the eighth centuries, the T’ang Code was revised and a new institutional framework was developed for the maintenance of an expanded empire, which now “stretched from southern Manchuria to the Pamirs and from Inner Mongolia to Vietnam” (Twitchett 464). These changes put the empire on quite a different footing from that which T’aitsung had bequeathed over half-a-century earlier, “an empire created by major (and generally successful) campaigns and preserved by the dynasty’s unchallenged prestige, by diplomacy and by no more than a thin defensive perimeter” (Twitchett 464). These changes came about in response to an increased foreign military pressure, mainly from the renascent Eastern Turks, the Khitan, and the Tibetans. In the face of recurrent conflicts with these powerful and well-organized neighbors, the T’ang regime was forced to assemble a large-scale defense system. To create an effective border defense against the Turkic Empires to the north and the Tibetan Empire to the west, Illustrious August originally established the jiedushi, also known as provincial military governors, as a way to solve the cost and response time of military defenses. Instead of sending out a large deployment of troops to the front lines, the empire needed a permanent standing army that would be supplied by locally supplied depots. They were also given autonomy to deal with incoming raids and attacks without having the consent of the Emperor or the Zaixiang, which, as it turned out, increased their power greatly. The discipline of these generals decayed as their power increased, and commoners began to resent them. Their grievances would explode into several rebellions during the mid-9th century, eventually ushering the jiedushi into “the political division of the ‘Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms’ period, a period marked by continuous infighting among the rival kingdoms, dynasties, and regional regimes established by rival jiedushi” (Ho 154). Many impoverished farmers, tax-burdened landowners, and merchants formed the base of the anti-government rebellions of this period. Soon, the empire was faced with the An Lushan Rebellion, and “its aftermath greatly weakened the centralized bureaucracy of the T’ang dynasty, especially in regards to its perimeters”(Ho 154). The T’ang dynasty’s continued desire for political stability amid the chaos resulted in the pardoning of many rebels, which resulted in the loss of political and economic control of the northeast region. The emperor ultimately became a puppet for the conquering garrison. The government also lost most of its control over the Western regions due to troop withdrawal to central China to attempt to crush the rebellion. Continued military and economic weakness resulted in further erosions of T’ang territorial control during the ensuing years. By the end, the rebellion was defeated, but at the expense of millions of casualties, heavy property damage, and a collapsed economy. The T’ang dynasty had finally fallen.

The idea of protection and security, the main driving force that led to the creation of the T’ang Dynasty, unfortunately became a double-edged sword. What was originally a promised necessity became a tyrannical tool. And while the T’ang Code was a key part of the T’ang Dynasty, serving as a “sophisticated legal system throughout much of history … [becoming] the fundamental basis for legal systems in other East Asian kingdoms during that time” (Ho 1), it also served as the empire’s greatest weakness, pushing the dynasty further into its own demise. It is agreed that there were several factors that contributed to the downfall of the T’ang dynasty and not just the T’ang Code. However, it is also true that the Code was meant to be the groundwork to guarantee the protection of the empire, its people, and China’s values. It brought the people together, generated an economy, provided a criminal system, punished those who took advantage of others and of the system, and even helped create a military force. It really did try. Unfortunately, many did not see it that way.

Bibliography

Benn, Charles. Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Ho, Norman P. “Confucian Jurisprudence in Practice: Pre-Tang Dynasty Panwen (Written Legal Judgments).” Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association, 2013.

Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume I: General Principles. Princeton University Press, 2019. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/64926.

Twitchett, Denis Crispin. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 3, Part 1 /, Sui and T’ang China, Cambridge University Press, 2008.