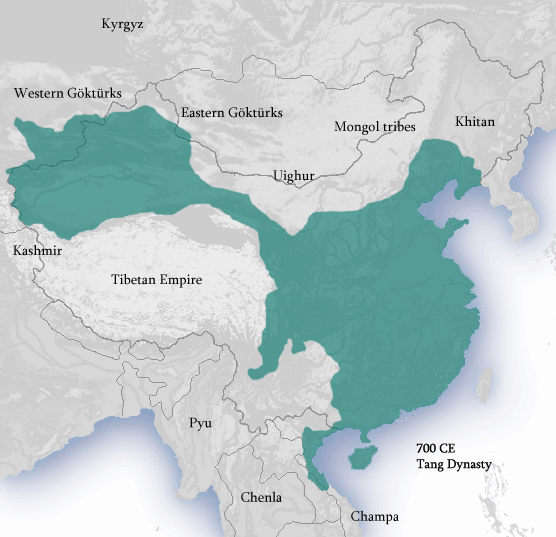

At the end of the Sui Dynasty (617 AD), Li Yuan (566-635), a Sui general and, later, the Duke of T’ang, joined the scores of rebels and marched straight for the Sui capital, Chang’an. His armies overwhelmed its defenses and took control of the city, where he would then, for six months, relegate the emperor to the position of Taishang Huang (or retired emperor), devise a series of plans, and, ultimately, establish a new dynasty that would last for almost three centuries and would rank alongside the Han dynasty as one of China’s two golden ages. 1 Why was it so successful? Because the Sui dynasty was plagued with death, forced labor, and heavy taxes. Many wanted to move away from it, and the people sought peace, prosperity, and safety. From the beginning, the T’ang dynasty was to be built on the promise of safety and protection.

When Li Yuan first rebelled and conquered land, he issued a series of lenient laws to relax the severity of the Sui dynasty system. Upon capturing the capital, to win the allegiance of the city’s population, he immediately announced a simplified set of laws in only twelve articles, modeled after the system of law created by the founder of the former Han dynasty, Han Kao-tsu (256-195), as an act of mercy to initiate his new dynasty. These laws, organized as a criminal code, reduced the number of crimes punishable by death. 2 It also described the “Ten Abominations”, or the ten most serious offenses a person could commit, and expounded upon the general principles of criminal law, justifying the punishment for each such offense.

This criminal code, entitled the T’ang Code, is said to have been masterminded by the T’ai-tsung emperor’s (627-649) brother-in-law, Zhangsun Wuji (594-659), who was one of the most powerful statesmen at the time.

It was believed that, during the reigns of the emperors Yao (2356–2255 BCE) and Shun (2294-2184 BCE), there were very few crimes due to the high moral standards that were followed in those days. The view of society expressed in the Code suggests that those ancient times were a golden age from which there has been a steady decline. With this decline, “the standards of morality were no longer sufficient to maintain order, and so laws became necessary. Thus morality and law are the two principal supports of society—morality first, but if it fails then punishment is the answer”. 3 The T’ang criminal procedure was generally logical, thorough, and provided quite a few protections for the accused, but, ultimately, the basic rule was that a criminal offense needed to be prosecuted through set rules of criminal procedure. Certainly one of the aims of the Code is to act as a deterrent – to fill the prospective law-breaker with fear for the consequences.

Unfortunately, the Code was too logical and specific. It was devised in such a way that one article couldn’t punish two crimes. Therefore, punishments and laws had to be used with extreme care. For example, when it came to execution, there were only “144 crimes punishable by the former and 89 by the latter”. 4 As such, any criminals that committed a crime outside of this category that warranted execution was not punished as severely.

This system of punishment proved to be quite problematic later on. For instance, there were certain crimes considered so heinous that they were specifically listed under Article 6, entitled “The Ten Abominations”. The crimes included within are “those that endanger the emperor or the state, those that are committed by subordinate members of the family or bureaucracy against their superiors, those that threaten the existence of the family, and even those that involve ‘black magic’ “. 5 The most serious crimes are the first two of the ten: plotting rebellion and plotting great sedition. The penalties for plotting rebellion or actually committing great sedition are the same: decapitation for everyone involved. Unfortunately, punishment also reached a great number of people who had no involvement in the crime whatsoever. The fathers and sons of the criminals were strangled; if the sons were fifteen years of age or less, they were enslaved by the state instead; and enslavement was also the punishment for the criminals’ mothers, daughters, grandfather, great-grandfather, and great-great-grandfather in the male line, grandsons, great-grandsons, and great-great-grandsons in the male line, his brothers and sisters, his and his sons’ wives and concubines, and any retainers or slaves belonging to the above. 6 Moreover, all of their goods and real property were confiscated by the state.

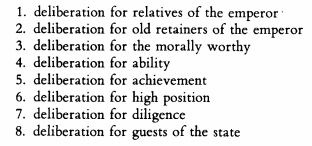

What’s more, under the provisions of the Code, the personal status of an offender could have a great effect on the conduct of a case, the sentence given, and, even, whether or not the offender was punished at all. The most important classification of privileged persons in the Code is of those who possess the qualifications that place them within one of “The Eight Deliberations”.

From the standpoint of the Code, the population of T’ang China consisted of three groups: the privileged, the commoners, and the inferior classes. With regard to crimes against the person, if commoners or anyone from the inferior class offended those of higher status, their punishment would be heavier than that of other classes. If those of higher status offended against members of the inferior classes, their punishment would be reduced.

The lowest in status were the slaves, who could be owned both by private persons and the government. Offenses against them by commoners were “generally punished two degrees less than were the offense against another commoner”, and offenses by slaves were “punished two degrees heavier than had the offender been a commoner”. 7 Fortunately, most of the laws that placed the inferior classes at a disadvantage are only concerned with crimes against the person. If the law covering an offense does not specifically provide for a heavier punishment where the offender is one of the inferior classes, the regular punishment is to be sentenced. 8 Thus the favorable treatment given to officials and nobles in the Code is balanced by the increased punishment meted out to the inferior classes. Indeed, the attitude expressed in the Code toward these individuals “equates slaves with property and goods”. 9 That is, they are viewed the same as domestic animals.

The Code, despite being quite logical, also attempted to emphasize harmony with the natural world through conformity with the yin-yang. The Code itself represents the yin, or the dark side of social control, in contrast with the yang influence of ritual, morality, and education. The best example of the importance of the yin-yang is “the restriction on carrying out the death penalty. Death was under the yin or negative power. Because of this, executions were carried out only during that part of the year when the yin influence was in the ascendant, the fall and winter seasons”. 10 Should criminals be put to death during the seasons when the yang power was rising, a poor harvest might result.

The Chinese cultural tradition is among the oldest and most lasting in the world; yet, it has also been blamed for many of China’s problems with its law system. Indeed, a look into Chinese legal history reveals that China lacked a rule of law system in its premodern past. Confucianism, the predominant state ideology and philosophical and ethical system that pervaded all sectors of life, is often seen as a school of thought completely contradictory to law. 11

As a result, T’ang political institutions and the T’ang Code underwent significant changes. The stress on law was carried through in practice: attempts were made to broaden definitions of criminal acts and to regularize legal procedure, and emperors were inclined to mitigate criminal punishments in general, both by legal reduction of penalties and by acts of amnesty. However, in cases of a willful violation of the law, the emperor continued to be very harsh. 12 With a continued imbalance of power and a partisan social hierarchy, the An Lu-shan rebellion (755-763) broke out and greatly weakened the centralized bureaucracy of the T’ang dynasty. The once centralized, rich, and powerful provincial order transformed into a struggling, insecure, and divided one, and later into ancient history.

Under Li Yuan, the T’ang successfully established political, economic, and military institutions that became hallmarks of the T’ang period, which, in turn, deeply influenced Chinese civilization down to the present century and provided the basic institutional models for the newly emergent states of East Asia. 13 Its law code was continued to be used until the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) revised it, where only half of it survived before the fall of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). 14 The T’ang Code was able to rule over many centuries and persisted through hardships; however, it was through those hardships that it became obvious that the current system of law needed to update. Therefore, what was once perceived as a perfect unity of legislative technique soon became an older version of the current law.

1 Twitchett, Denis Crispin. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 3, Part 1 /, Sui and T’ang China, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

2 Ibid.

3 Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume I: General Principles. Princeton University Press, 2019. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/64926.

4 Benn, Charles. Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty. Greenwood Press, 2002.

5 Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume I: General Principles. Princeton University Press, 2019. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/64926.

6 Ibid.

7 Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume II: Specific Articles. Course Book ed. Princeton University Press, 2014. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/33726.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume I: General Principles. Princeton University Press, 2019. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/64926.

11 Ho, Norman P. “Confucian Jurisprudence in Practice: Pre-Tang Dynasty Panwen (Written Legal Judgments).” Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association, 2013.

12 Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume I: General Principles. Princeton University Press, 2019. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/64926.

13 Twitchett, Denis Crispin. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 3, Part 1 /, Sui and T’ang China, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

14 Benn, Charles. Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Bibliography

Benn, Charles. Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Ho, Norman P. “Confucian Jurisprudence in Practice: Pre-Tang Dynasty Panwen (Written Legal Judgments).” Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association, 2013.

Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume I: General Principles. Princeton University Press, 2019. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/64926.

Johnson, Wallace. The T’ang Code, Volume II: Specific Articles. Course Book ed. Princeton University Press, 2014. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/33726.

Twitchett, Denis Crispin. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 3, Part 1 /, Sui and T’ang China, Cambridge University Press, 2008.