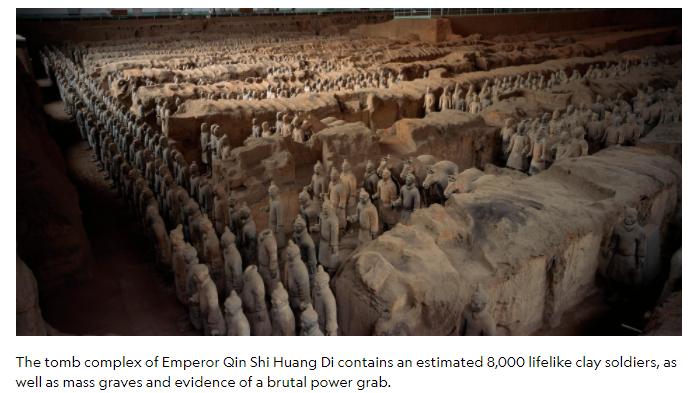

The first time I had heard of, or even seen, the Terracotta Army was in the movie, the Mummy Rises Again. At that point, I was a child merely in awe, watching as the lifeless, ceramic statues came to life and attacked the main protagonist; however, that’s all it was then – just another action movie that was in the back of my mind. I had no clue that I would, someday, read and learn that these statues are, in fact, real. I remember them being put with the tomb of an emperor (who I later found was the first Emperor Qin), which was built much like an underground city. I knew that many of these figures were built, although I didn’t think there were thousands. Nonetheless, their sudden reappearance into my life made me wonder…

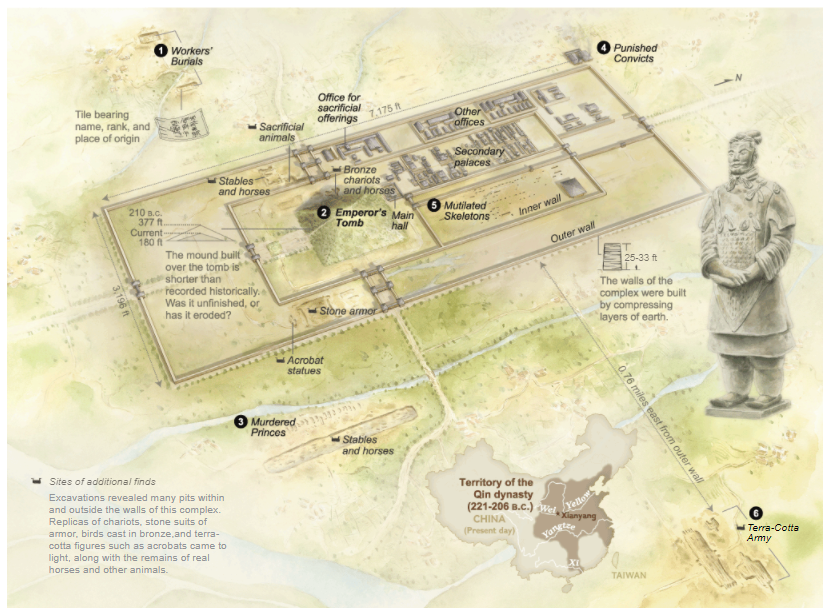

These figures were modeled after the people of China. Armin Selbitschka, Assistant Professor Faculty Fellow at NYU Shanghai, extends on this, explaining that different stances each figurine had represented different occupations; “Servants, for example, are either kneeling or standing” (29). Small models of different objects were built to let spirits interact and use them even in the afterlife. These tombs were a part of the Qin Empire, located in Mt. Li where the first emperor and around 700,000 of his men began construction. Craftsmen layered the exterior of each coffin with bronze, and adorned the tombs with different empire goods/items that they believed spirits would need after a death. As for the reason why there were so many figures, the Terracotta Army was built to serve the emperor even in the afterlife. Ultimately, craftsmen and even criminals were trapped and buried in the tomb, potentially to hide what was buried.

While the construction of the tomb was never finished, it is still very remarkable to know what they intended to achieve despite the limited tools and supplies they had at the time. Each figure had its own features and expressions; bronze weapons, crossbows, and models of daily objects were crafted to seal them along with the tomb; the walls were beautifully carved with native artwork. Even figures of living beings, like horses, were created to accompany the Emperor in the afterlife. So much thought was put into this burial, showing just how much the Chinese valued and respected the dead, treating it not in mourning but rather as a ceremony.

Bibliography:

Riegel, Jeffrey, “Archaeology of the First Emperor’s Tomb” (2 parts). Lectures 3 and 4 in the series Arts of Asia, by Asian Art Museum.

Selbitschka, Armin. “Miniature Tomb Figurines and Models in Pre-Imperial and Early Imperial China: Origins, Development and Significance.” World Archaeology 47, no. 1 (2015): 20-44